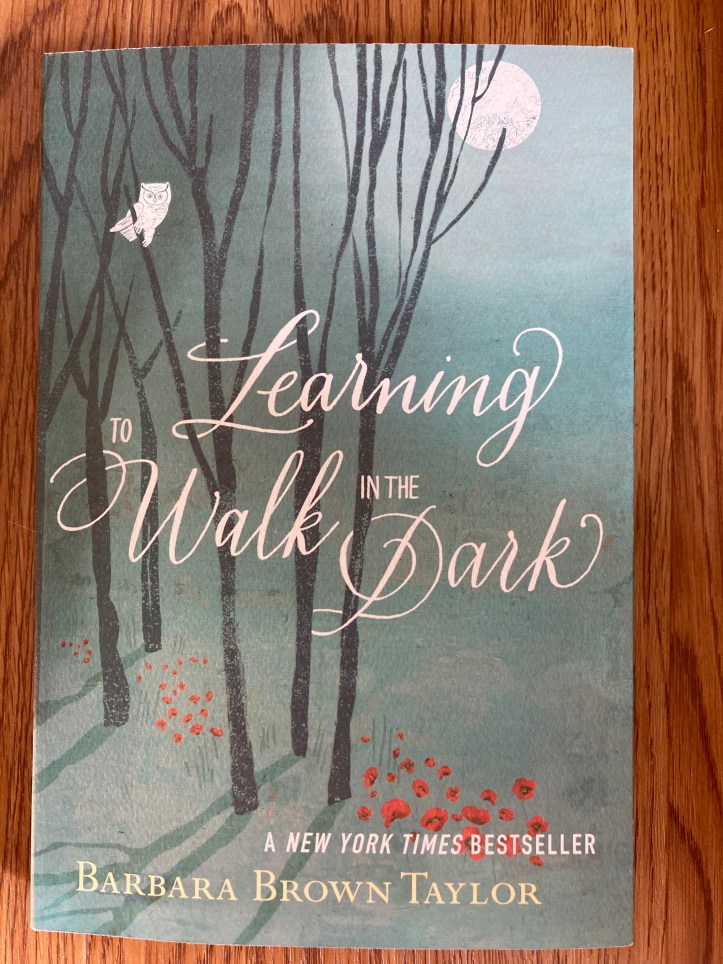

These days I’ve been reading Learning to Walk in the Dark by Barbara Brown Taylor, the assigned book for April’s cohort. I’m aware of the irony in the title as Winnipeg days are getting longer and the glorious sun is beaming into my window, reminding me that spring is near. Still, the recent time change has temporarily darkened the early morning once again, allowing me to light a candle like I did during the pre-solstice mornings of November and December. At least for a short while.

Call me crazy, and maybe it’s the poet in me, but I love the darkness. Candles can be lit. It’s a time for stillness and introversion. For someone who can be quite social (and then exhausted), the solitude feels like a balm. An opportunity to rest from my never-ending hunger for the outer world to tell me I’m ok and maybe even liked. When I first left my teaching job where I talked all the live-long day, the quiet in the dark was a huge relief. I no longer had to break my day up into 45-minute hyper-alert segments, yakking away in what no doubt sounded like a “Charlie Brown teacher voice” to my students.

So when I saw the title of our next book, I smiled. “I’m on board Barbara Brown Taylor! Preach it!”

Taylor wrote about being terrified of the dark as a child, and I scanned my memories. I had no such terror, and still don’t. I didn’t wake up screaming or beg for night-lights. (Were nightlights even a thing in the 60s?) Who’s afraid of the dark? Not me. And yet, a few memories surfaced which called my bravado into question.

The basement of my childhood home had a cold storage room, a “kammer” in German. Like most Mennonite homes of the day, its shelves were lined with home canned fruits and vegetables, even honey, and my mom would often ask me to fetch one for our supper. Though the errand would have taken only a few seconds, that dark, dank room terrified me. It was unlike any other room in the rest of our basement. There was no fun ping-pong table or TV with the latest from Walt Disney in there, no comforting washing machine or dryer, and no light switch. Just rows of cold jars in a room that had an odd smell. And weren’t there centipedes in those corners? Is this what a mausoleum was like, I wondered? I was away from everyone down there, alone. Who was I anyway? Taking the steps two at a time and clutching the jar I’d been sent for, I couldn’t race upstairs fast enough.

Taylor writes about an essay in a book called Let There Be Night. The author, James Bremner, had his version of childhood terror in the darkness when he had to take the family’s empty milk bottles down to the bottom of the driveway for the milkman to swap out in the morning. With no streetlights or porch lights in his Scottish village, it was a journey into the pitch blackness that required all the courage he had. And it never got easier.

Years later, he observed that the bravery it drew out of him stayed for the rest of his life. His voyage into the darkness had prepared him well. All children, he wrote, need a place to practice courage — a “widespread, easily obtained, cheap, renewable source of something scary but not actually dangerous.”

I like that. Reframing the terror I felt in the “scary but not actually dangerous” kammer as an early exercise in courage makes sense. No doubt my courage muscles grew there.

Or maybe they didn’t. Once childhood dissolved into adolescence, I confess I was more of a wimp when the pain of menstrual cramps forced me back into a different kind of basement. I remember sitting on the school stairs and beseeching God. It wasn’t a prayer for Divine help amid my trial, or for wisdom to grow there. It was just one desperate prayer on repeat, “God, take this away.” I wanted to be freed from my suffering, nothing more. A decade later when soon-to-become-chronic headaches began, I lamented my request to God again. What good is darkness? Where was the exit ramp this time? Just give me the happy stuff please.

The great Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn has a line I love, “You gotta kick at the darkness till it bleeds daylight.” But at such a young age, I didn’t know a wrestling match was required. Or, an even more absurd thought, that there was treasure to be mined in the dark if only I would take some deep breaths and look around. Taylor confessed the same blindness, “Without benefit of maturity or therapy, I had no way of knowing that the darkness was as much inside me as it was outside me…”.

Taylor writes that “darkness” is shorthand for anything that scares us, and my list is long. There’s the big fears like war, climate change, the suffering of the poor in Winnipeg’s homeless camps…but honestly, the fears that grip me the most are much more local. At the top of my list is unresolved relational conflict (ugh) but there’s also fear of chronic pain, the loneliness of insomnia, the diminishments of aging, loss of purpose or meaning. In my darkest nights, I fear God is absent or even worse has forgotten me, and that my prayers really are just drifting back at me like so many dead leaves.

Like many others in the West, the religion I cut my teeth on reinforced a “joy only” outlook on life. “God is light and in him there is no darkness at all.” (1 John 1:5) Read superficially, these kinds of verses can reinforce the myth that we need to be sunny-side up for God 24/7. At least that was what happened to me. When darkness fell on our family in 1968 with the death of my sister, there was nowhere to lament, so we all fell silent. Though the church no doubt cared in many ways, we weren’t given theological skills for operating in the dark. As a teen, if I was struggling, I thought the only goal was to pray my way out of it asap. As a budding Enneagram 2, I used religion to become a helpful, “good” person. With confidence, I sang “Jesus is the answer…” with my high school friends, happily ignoring the questions that were already growing in the dark. So much bravado. And so ill-equipped for the suffering life hands to us all.

Taylor calls this version of faith “full solar spirituality”. It’s a “kind of spirituality that deals with darkness by denying its existence or at least depriving it of any meaningful attention.”

The faith community I’m part of does not practice “full solar spirituality”. We used to joke that the Good Friday service was our favorite of the year. I’ve always been encouraged to embrace the hard stuff. And yet, I confess I’m still lousy at walking in the dark. My first impulse is to feel around for the nearest light switch and run, or at least distract myself. I get “seize the day” but… “seize the night”?! Who am I kidding? Despite my love of candles in the silent dark, full solar spirituality is more hardwired into me than I once thought.

Taylor writes that there is a light that shines in the darkness which is only visible there. Like the moon, it may wax and wane, but it is always there. As I read her book in the quiet mornings, I pondered the so-called dark emotions I’d rather not have and noticed my tendency to resist them. Fear. Sadness. Shame. Depression. Loneliness. Anger. I’m not usually even aware of them in real time! I notice my tendency to appear “good” (no shadows please), but God (and those closest to me) are not fooled. I’m not the sunbeam I’ve tried to be for so long. Instead of resisting, I’m actually being invited to rest in all that is unresolved in my life. And so I take a breath.

Step 1 of learning to walk in the dark, says Taylor, is to “give up running the show. Next you sign the waiver that allows you to bump into some things that may frighten you at first. Finally you ask darkness to teach you what you need to know.” My old prayer, “God take this away,” simply won’t do anymore. It didn’t help at 13, and it doesn’t at 62 either. I’m being invited to let that prayer go.

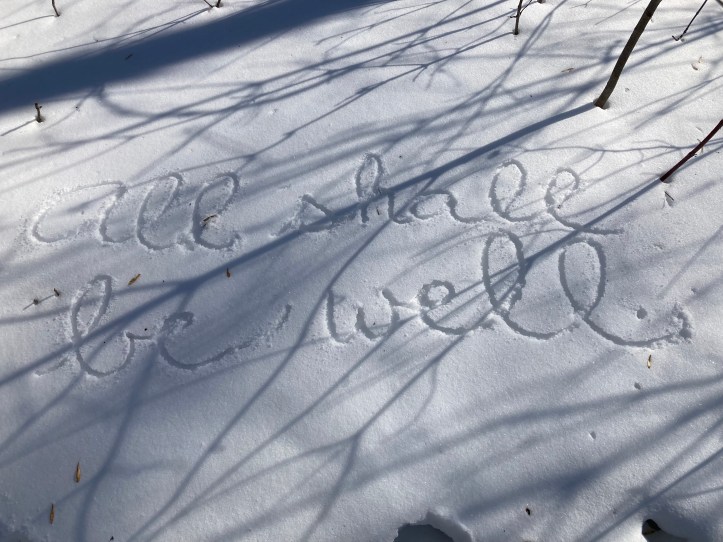

As my second cohort approaches, I’ve been practicing just breathing deeply, letting all the unresolved places of my life be. Perhaps “I’m confused”, “I’m angry” or even “I’m despairing” can be a full-sentence prayer in the dark. Maybe between breaths, I can stay curious as I listen for what God will say next. As Thomas Merton prayed, “Therefore I will trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

Another memory surfaced as I wrote this blog. I remembered being curious about the jars of honey stored in the dark kammer. Pressing pause on my chronic terror for once, I opened one and dipped my finger in. I closed my eyes in delight as the granular bits of honey slowly melted on my tongue. Returning upstairs with the requested jar of canned goods, I was also armed with new knowledge that the darkness can also hold golden treasure. This time, I walked rather than ran.

Such a great reflection. Perfect for Lent and every other season really. Glad you’re back in the blogosphere Lyds

LikeLike